Amalgam的超級模型車 (轉文)

The Bizarre And Exclusive World Of $20,000 Toy Cars by Forbes

Sandy Copeman and his team of master craftsmen in Bristol, England, build cars that enthusiasts covet: the 1938 Alfa Romeo 8C 2900 Mille Miglia, 1938 Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic, 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO 3589GT, 1961 Jaguar E-Type Series 1-3.8 Coupé and 1957 Porsche 356A Speedster, to name a few. Each car is an impeccably detailed, beautifully painted handmade masterpiece—and costs a fraction of what these vintage vehicles and contemporary exotics would sell for at auction or through a dealer.

Then again, they’re also one eighth the size. That’s because Copeman’s company, Amalgam Collection, specializes in building meticulous scale models of vintage and modern automobiles. In fact, without a visual clue to reveal the relative size, it’s often hard to tell Amalgam’s miniature masterpieces from the real thing. “That’s the goal,” says the 65-year-old founder. “If you can take a high-resolution photograph and put it in front of somebody, and they have no idea whether they’re looking at a model or the real car, then we’ve done our job.”

Some of Amalgam’s models even perform like their full-size cousins. For example, the new 1:8 scale McLaren Senna, which costs a little more than $13,000, features headlights, taillights and hazards that light up via remote control. The doors are motorized and can move up and down on command.

Copeman’s interest in tinkering developed when he was a teenager. He built a reflecting telescope when he was 14, as well as a couple of electric guitars. One of his greatest passions was modifying and racing mopeds. “I used to strip all the steelwork off them and turn them into lean, mean machines and then race them in my parents’ garden in London,” he recalls with a chuckle.

After dropping out of school at 17, Copeman became something of a nomad: “I was a young hippie and traveling throughout Europe and North Africa. That’s what anyone with a sense of adventure would look to do at the time.” He eventually settled in an artists’ colony in Somerset, England, called Nettlecombe Studios, which was established by British painter and printmaker John Wolseley. At Nettlecombe, Copeman found his vocation as a model maker after being asked to create scaled buildings and villages for an architecture firm.

He moved to Bristol in the late 1970s, and within a decade he and three of his colleagues had formed Amalgam Modelmakers. “After six years [working for a small model-making company], our skills and confidence had grown to the point where we decided to start our own partnership making architectural models for the likes of Norman Foster and other rising starchitects, as well as industrial designers like James Dyson,” Copeman says.

Amalgam began designing model cars for Formula 1 racing teams in 1995 after approaching Jordan Grand Prix, a nascent F1 constructor. “It was the crystallization of a passion for motorsport that I and several members of our team had, especially for Formula 1,” Copeman says. As a kid he was a fan of Jim Clark, one of the greatest Formula 1 drivers of all time, and was an enthusiastic slot-car racer at age 15. “My passion for 1960s Formula 1—and car design in general—was just waiting to find an outlet,” he says. “We got the opportunity to make a first model under license [the Jordan 196], then got a deal with Williams Formula 1 in 1996 and finally with Ferrari in 1998.”

In 2004, Amalgam split into two entities: Amalgam Modelmakers and Amalgam Fine Model Cars; one team made one-off architectural models and the other produced scores of miniature cars. “I had ambitions to build a brand making the best model cars in the world,” Copeman says. “That involved a degree of risk taking and a mission not shared with my partners.” The two companies remain deeply connected, though. “We operated out of the same building for several years and are still good friends today,” he insists. But Copeman has no financial interest in the original company. “We do share ownership of our original workshop,” he adds.

From 2006 to 2007, Ferrari’s then-president, Luca Cordero di Montezemolo, commissioned Amalgam to make miniatures of current and classic road-going Ferraris. “We started with the 250TR, as opposed to the GTO,” says Copeman. “A Scaglietti car.” It took some time, but Lamborghini, McLaren and other automakers eventually wanted models of their vehicles as well. That’s when business really took off.

Today the company, which Copeman renamed Amalgam Collection in 2016, has revenues around $10 million a year, building more than 500 models a month that range in price from $685 to upwards of $150,000, depending on size and the amount of detail. It employs more than 200 people and has two manufacturing facilities outside of Bristol, in Chang An, China, and Pécs, Hungary.

“We manage the design and tooling of the models in Bristol,” Copeman says, “but most of the models are fabricated in China and Hungary. We are also increasingly making one-offs and doing special projects out of Bristol.”

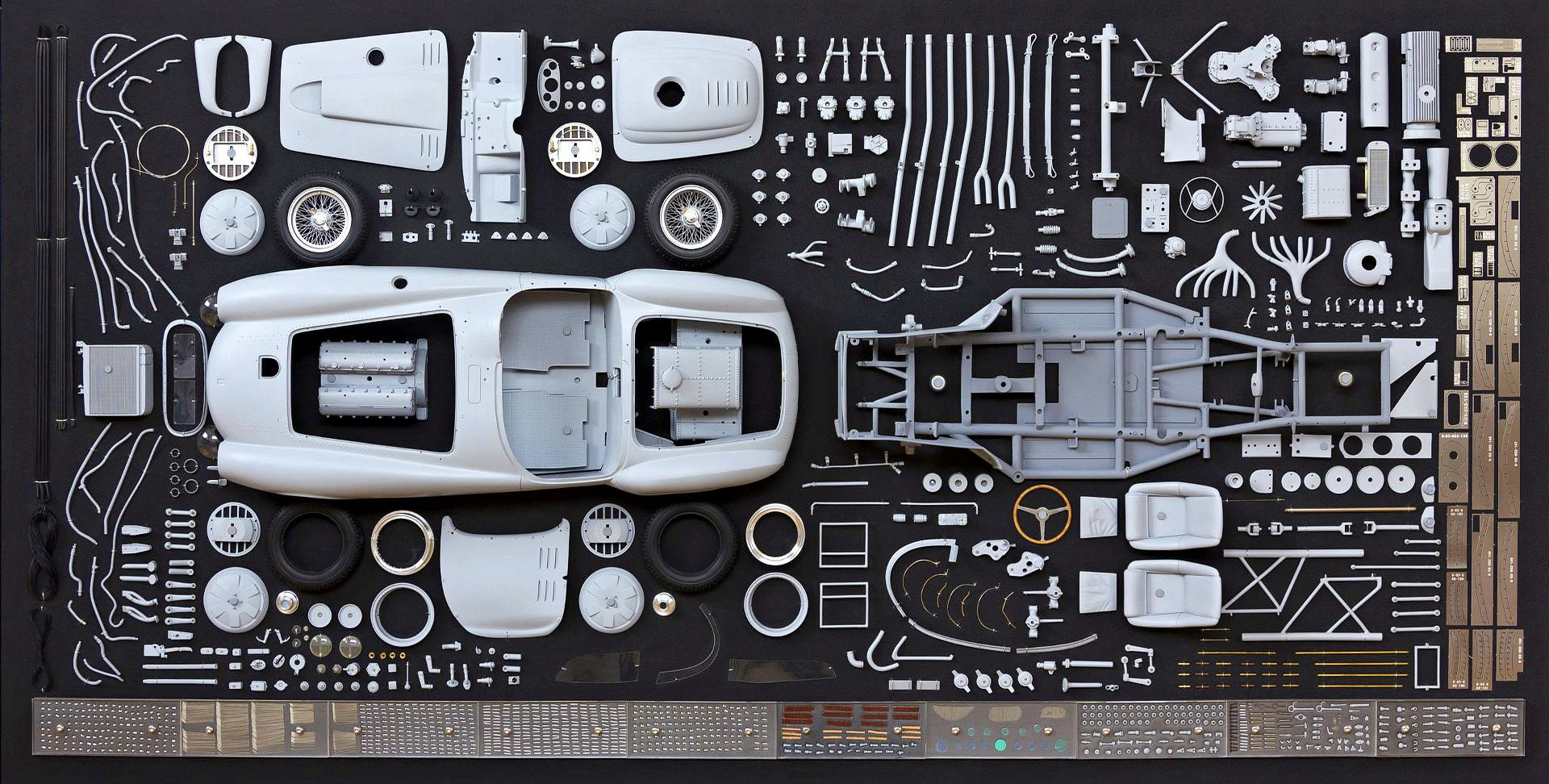

So how does a model go from concept to finished form? In the case of newer cars, the Amalgam team works from original CAD drawings, obtained from the manufacturers, to produce minutely accurate drawings of each car part. “[By using the CAD data], all the parts fit together and connect together in a good, solid, well-engineered fashion,” Copeman says.

Designs for models of classic cars are formulated from digital scans of the car and hand measurements. “We also work from 600 to 800 photographs,” Copeman says. “We use them to make sure everything is dimensionally correct.”

Once the design is set, it is meticulously scaled down to bring the details to life in miniature. Molds are created for the individual parts, and metal, carbon fiber or rubber is used to create each piece of the puzzle, while some are produced by 3-D printers.

After the parts are cast, they are washed, cleaned and sanded. Then each set of parts goes through a fettling and fitting process to ensure they go together perfectly. Afterward, the models are primed, spray-painted and polished. Decals and printed finishes are applied, then subassemblies such as engines, wheel hubs and suspensions are built, followed by final assembly. “About 90% of the skills we use are very traditional,” Copeman says of the process, most of which is done by hand and which he likens to fine watchmaking. “Ten percent are modern.”

Producing the design molds takes between 2,500 hours (for, say, open-wheel racers) to 4,500 hours for complex classics, and it takes another 250 to 450 hours to make each model. “For example,” Copeman says, “The Ferrari LaFerrari takes about 3,500 hours to develop and another 350 to build.”Amalgam’s elite clientele still consists of Formula 1 teams, drivers and managers, but it also includes famous collectors. Sylvester Stallone bought a limited edition 1:8-scale Ferrari F1 car from the early-2000s Michael Schumacher era. Ralph Lauren commissioned 17 models of cars from his collection while they were on display at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, including a Jaguar D-Type, like the model whose shark fin blazed a triumphant trail at Le Mans in 1955, 1956 and 1957. Swiss watchmaker Richard Mille commissioned several 1:5-scale models of cars from his collection, which contains some of the rarest and most significant vintage race cars, including Bruce McLaren’s first Formula 1 car (the M2B from 1966) and the Ferrari 312B, which won the 1970 Italian Grand Prix and was driven by Mario Andretti.

Surprisingly, Copeman does not collect cars himself. For him it’s all about the personal experience of riding or driving. “I have owned some lesser but interesting vehicles along the way, such as a 1950s-era MG Magnette, and I’ve had some memorable drives, like the 160 mph race up the M1 motorway in a Sunbeam Tiger against a Jaguar E-Type,” he says. “But I’ve owned many more motorcycles than cars.” His everyday ride is a Mercedes CLS Shooting Brake: “It’s a fun drive if you want to push it a bit.”

Besides, he can build any car he wants—just by dreaming small.