The Death of Italian Coachbuilding (轉文)

實在難以相信Bertone這么偉大的一個汽車設計公司會倒閉。

Carrozzeria Bertone, the very last of the great Italian coachbuilders who led world car design from 1946 to circa 1986, was forced to close its doors this year, 102 years after its founding in Turin, Italy. The now-unfamiliar term “coachbuilder” applied to enterprises, most of them simply artisanal workshops, that designed and constructed bodywork for automobile chassis. For the first half-century or so of the automobile’s existence, carmakers typically created only the engine and chassis of their products, relying on separate entities to design, build, and mount bodies on those chassis.

Even companies as big and powerful as Ford and General Motors relied on outside body builders up into the Thirties: Briggs and Murray for the former, Fisher Body for the later. Eventually, of course, those firms were absorbed by their clients, but bodies for prestige chassis like Packard, Rolls-Royce, and Isotta-Fraschini were made by outside specialists right up to the outbreak of World War II.

After the war, there was really no need for coachbuilders in the United States, as there were in-house design and body manufacturing groups for all the remaining brands. Most of the prestige makes of the Thirties—Cord, Duesenberg, Marmon, Peerless, Pierce-Arrow—were victims of the Great Depression, and there were simply no clients for firms like California’s Murphy Body, which had built more than half of all Duesenberg bodies. A few coachbuilding houses remained in Britain, but only Rolls-Royce, Bentley and Daimler had need of them.

In France, world center of car design 1919-1939, the postwar Communist government impoverished the few remaining French body design and construction firms, not allowing them to buy metal and other materials they needed. Those same restrictions were applied to the remaining high-quality, low-volume chassis makers, and by the end of the Fifties Delage, Delahaye, Hotchkiss, and Talbot were gone.

So that left Italy, whose strongly left-wing governments were more interested in jobs for coachbuilders’ workers than in punishing their rich customers. That attitude was fortuitous for firms like Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, and Maserati, which could sell extravagant cars to wealthy customers all over the world. Perhaps only one or two cars would go to the Philippines or Argentina, or any of a hundred other countries, but those few sales kept skilled craftsmen employed and their families housed, fed, and healthy.

Italy has always been a country where beauty and elegance are valued, where presenting “una bella figura” is important across a wide cross-section of society, where the arts mattered as much to people of modest means as to the very wealthy, where mundane objects are often the subject of careful and thoroughly considered design. I remember being fascinated by the shape of cupboard hinges and door handles in my hotel room the morning of my first day in Italy in the Sixties, and then finding endless cases where the American equivalent would be sturdy, well made, and practical but totally devoid of the aesthetic interest manifest in the Italian object.

The Italian concern for individuality carried over even into very cheap cars in a way not seen in other countries. Americans have often embellished their Fords and Chevrolets with add-on accessories, but many Italians in the Fifties would have completely new body panels made for their Fiat 500s, the little cars Italians called “Topolinos.” And when Alfa Romeo, Fiat, and Lancia—then rivals, not part of the same group—embraced unitized body-chassis structures and eliminated chassis frames, they went to the trouble of making coachbuilder platforms so people could go to their neighborhood body shop and have an individual body made.

There were literally thousands of places to have bodies, or parts of them, made by skilled workers. One of the most prolific Italian designers, Giovanni Michelotti, is said to have had more than fifty individual cars on display at the 1953 Turin Motor Show. For about $35, a private client could have a design for his Fiat from the same hand that had created some of the most dramatic one-of-a-kind Ferrari bodies.

There were, of course, a few coachbuilders who stood far above those local shops. Most of the best known were in Turin: Carrozzeria Ghia, which built many Chrysler show cars (and whose name adorns the Alfa Romeo 6C2500 shown here); Carrozzeria Pinin Farina, set up in 1931 to make a spectacular body for a Cadillac V-16 chassis; and Carrozzeria Bertone, a tiny operation until the Fifties, when “Nuccio” Bertone, son of the founder, took a huge risk and agreed to build 1,000 coupe bodies for Alfa Romeo. There were two famous houses in Milano, Carrozzeria Touring, specialists in aerodynamics and lightweight structures—their slogan was “air is the obstacle, weight the enemy”—and Carrozzeria Zagato, whose founder came from aviation.

Ghia was purchased by Ford in the Sixties, when the American company was involved in racing, special models, and making concept cars, but its Turin facilities were closed a long time ago, and the name is just a trim-level badge for ordinary Ford passenger cars. Touring went broke more than forty years ago, and most of its archives were burned as its buildings were cleared out. Zagato exists, making small numbers of special body variants of expensive cars like Aston Martin and Ferrari.

The decline and fall of the great design and small-volume production houses comes from two principal causes, one industrial, the other sociological. The industrial matter is quite simple: all carmakers in the developed world have their own in-house design teams, quite often led by an imported chief designer from a well-established manufacturer. That is true for the Korean group that makes Hyundai and Kia cars. Peter Schreyer, a German with a distinguished past with the Volkswagen Group, was hired first to put some spark into Kia. He was so successful that he was named head of all design for both nameplates in January 2013. Fiat do Brasil has a design team headed by Peter Fassbender, another German who had extended experience in Italy. These successful professionals have taught successive generations of native designers the practices of the most competent car design departments in the world, so there is no longer any advantage for a company to go to Italian firms, as was the case as recently as the 1990s, when Peugeot and Citroën relied on Pininfarina and Bertone, respectively. Today a Frenchman, Jean-Pierre Ploué, heads the design teams for both makes, in a single dedicated facility near Paris completed in this century.

The sociological problems come from the fact that Italy is still organized around families, not corporate entities. Yes, Fiat is the biggest company in the country, but it is essentially the fiefdom of the founding Agnelli family, which has firm control over the holding company that pulls all the strings. And the design houses were dynastic family operations as well, all of them having followed the traditional pattern of such firms: the founder creates something promising, the second generation develops and expands the entity, and the third generation, never having had to struggle or build anything, dissipates the accrued fortunes.

Consider the Pininfarina venture. Battista Farina worked for his older brother’s company, Stablimenti Farina, until 1931, when he set out on his own. Battista was a very small man, perhaps five feet three inches tall, but a giant in talent, a bundle of energy, nicknamed “Pinin” (“Shorty” in English). He became world famous, to the extent that he was granted the right to change his family name to Pininfarina. That may sound distinguished to us, but literally translated, it’s “Shortyflour.” Battista’s two children, a daughter and a son, inherited the firm, but in the typical Italian manner, it was the son, Sergio, and the daughter’s husband, Renzo Carli, who took over from the founder in 1961, the year the family name changed. The two men did a great job in expanding the company, its production capabilities—in addition to classics like the Ferrari 250GT shown here, the house not only designed the body of the Peugeot sports models, it built them—but when they retired, the decline and fall began.

Sergio Pininfarina (pictured here with Enzo Ferrari) had three children, a daughter and two sons. The eldest, Lorenza, was by far the brightest of the three, but because of her gender and Italian machismo, she was relegated to public relations while her less-capable younger brother was accorded control. When he was killed in a scooter accident after putting the company in debt to banks to the tune of a couple of hundred million euros to fund expansion that never came, the youngest—male—child was given the reins. Result, the company still has work, the Pininfarina family interest is less than ten percent of the total capital, and the prospects for the future are bleak.

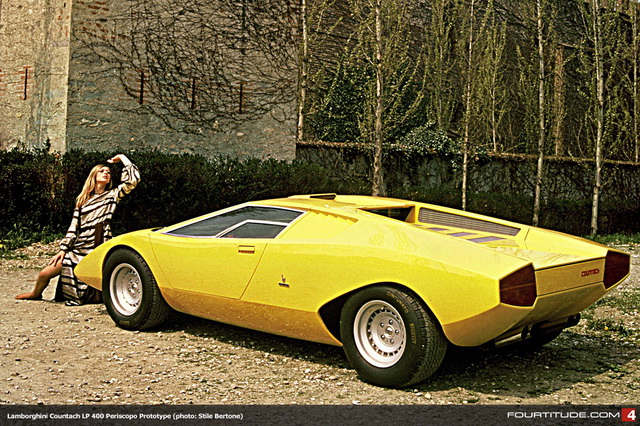

As they are now for Carrozzeria Bertone. The founder, Giovanni, ran a nice little business; his son Nuccio (diminutive of Giovanni) turned it into a really excellent mid-size business. (He’s pictured here with the 1963 Corvair Testudo prototype.) Nuccio hired only the most talented designers—Mario Revelli de Beaumont, Giovanni Michelotti, Franco Scaglione, Giorgietto Giugiaro, Marcello Gandini—and gave them public credit for their work, unlike most other design houses, where the talent was anonymous and the families took credit. But Nuccio, who died in 1997 at age eighty-three, had only two children, both daughters. So, in the traditional manner, given that the girls had no particular design abilities or interest, their husbands were given direction of the company and proceeded to run it into disaster, losing the production facilities Nuccio had built to Fiat, and his widow, Lilli, took over amid TV-series-level drama. It was too late, and the company that had never had a penny of debt during Nuccio’s lifetime is bankrupt today.

Turin has been known for the metalworking skills of its populace since the Middle Ages, when it made the most elegant and practical of suits of armor, and it grew into the industrial powerhouse of Italy in the twentieth century, because at every street corner there were people who surpassed the abilities of highly regarded specialists in other lands. That is gone today for the most part. There are still large numbers of capable people, but there is little focus for them. Giorgietto Giugiaro, a great designer who did his best work under the tutelage of Nuccio Bertone, founded his own studio, Italdesign Giugiaro, with partner Aldo Mantovani, an engineer of great talent. Giugiaro of course wanted to leave the company to his son, Fabrizio, even though his daughter was more focused on design than the fun-loving young man. In the end, the entire firm was acquired by the Audi division of the Volkswagen Group and is now internal to that huge multi-make company.

There are still plenty of extremely good Italian car designers—Walter de’Silva, who revived Alfa Romeo style some time back, is head of design for the Volkswagen Group, for example, but there is not a single fixed place to go, without reflection, in Italy for car design. The enfeebled firms have found work in China, where literally hundreds of car manufacturing firms were created in Deng Xiaoping’s industrial revolution that followed Mao’s destructive “Cultural Revolution.” But the Chinese have always been quick to learn and to innovate, so they will not long be interested in foreign design input, just as the Japanese, who leaned heavily on Italy in the Sixties, are no longer clients for the moribund Italian design houses.

In a sense, all this is sad, but in truth it is the way of the world. Things change, and those who expect the status quo to persist are always disappointed because it never does. Yes, Italy was vital and central to car design in the second half of the twentieth century, as France was during the two decades between the two world wars, and as the United States was for volume production car design from 1920 to 1955. People will always remember the great works of Pinin Farina, Nuccio Bertone, Luigi Segre of Ghia, and the great creators they employed, but the passion, the drive, the intensity has gone. We can regret, lament, celebrate the past, but there is no foreseeable future for Italian car design.

Pininfarina responds:

We read with great dismay the article “The Death of Italian Coachbuilding” (March 31, 2014) by Robert Cumberford, respected journalist who has been following Pininfarina since decades. This is the reason why, this time, we are very astonished by the many inaccuracies and false statements in his story. Firstly, we are disappointed by such little respect towards the Pininfarina family. Unfounded personalized criticisms, such as the ones addressed to Mr. Andrea Pininfarina, and statements about Mrs. Lorenza, do not deserve any comments. The role of the third generation has been – and still is – central for the Company. Under Paolo Pininfarina’s chairmanship, the Company is perpetuating the image of a brand that is still perceived as synonymous with excellence. Pininfarina continues to cooperate with a great number of automakers and has undertaken new collaborations expanding the range of business from automotive to boating, aeronautics, industrial design, interior design and architecture, as evidenced by the many recent successful projects in the United States, Latin America and Asia. The global crisis occurred in the latest years, in particular to automotive industry, is an undeniable fact. However, the crisis did not hit only companies organized around families, as confirmed by the bankruptcy of giants like GM and Chrysler. Pininfarina has gone through difficult years as many others but continues on its path offering the world its interpretation of creativity, as borne out by the Gran Lusso created with BMW and the acquisition of new customers from among the world’s top 10 car manufacturers. Growth in the engineering sector has been achieved mostly in Germany and Asia, in particular in Japan and India. On the Italian market, important projects underway in collaboration with Ferrari and its Styling Centre are evidence of the strong, long-lasting ties between the two companies. Besides design, Pininfarina provides all-round support to automotive companies by engaging in a variety of activities: engineering, product development, testing, prototype construction. More generally, we do not share Mr. Cumberford’s opinion when he argues that “there is no longer any advantage for a company to go to Italian firms” . Prestigious clients such as Ferrari and BMW continue to rely on Pininfarina’s creativity. The models on display in Geneva this year showcase the role of Pininfarina as the standard bearer for the aesthetic values of Italian design in the world and strengthen the brand, the firm’s true distinctive character. The new Ferrari California T, together with the F12berlinetta, the FF and many other recent projects, are part of a history that has generated the finest cars of all times through an evolution that started over 60 years ago and shows no sign of waning. And the Gran Lusso confirms our mission not only as global designers, but also as makers of exclusive high-quality cars. Mr. Cumberford is right when he says that the era of coachbuilders as contract manufacturers is over. However, today Pininfarina continues to dedicate resources and talents to the creation of unique pieces, reinterpreting its artisan roots. The dream of the Ferrari Sergio is becoming true for a few collectors thanks to Pininfarina skills and experience. At our style and engineering center in Cambiano we continue, as ever, to conceive, develop and manufacture one-off models and small series. It’s a job that is so noble and so peculiar to the Turin area. It is a return to our origins, to a niche that is fully keeping with our vision, our history. Pininfarina, in essence, is still a strategic partner with which the internal OEM styling centers continue to compete on all the proposed designs. Being considered a reference point in style is testified by the many awards received also in recent times, such as the 2012 Interior Design Award of the Year for the Cambiano, the Best Design Study 2013 for the Sergio, the GOOD DESIGN™ Award 2013 and German Design Award 2014 for the BMW Pininfarina Gran Lusso Coupè. Despite the “de profundis” sung by Mr. Cumberford, Pininfarina is more alive than ever. We kindly invite all Automobile’s readers to follow us on www.pininfarina.com and www.facebook.com/PininfarinaSpA. There they will see how vital our company is.